I learned last Thursday that conservation easements in Boulder County are incredibly valuable—if you’re a real estate speculator. Here’s what you do: Find a nice piece of land that’s under conservation easement. Buy it (relatively) cheap because the county has supposedly placed limitations on how it can be used. Wait a while, then hire a lawyer. If the lawyer can convince county attorneys that there’s a chance he could have part of the easement overturned in court, the county will rewrite it to let you do whatever you want. Sell the property for several times what you’ve paid for it, and bingo. You’ve just realized the value of conservation easements in Boulder County.

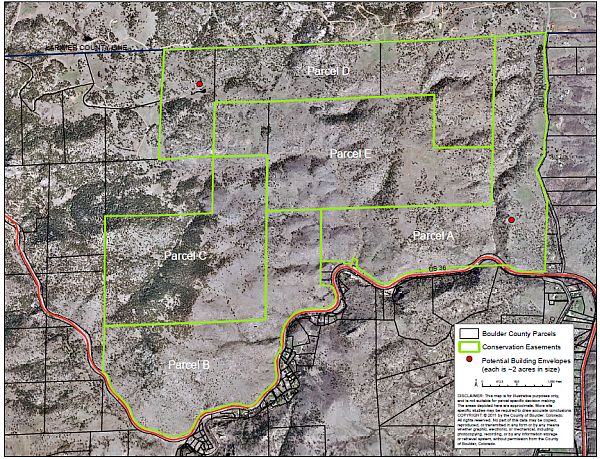

Unfortunately, the value to Boulder County taxpayers—the people whose money the county uses to purchase these contracts—is harder to see. I wrote previously about a proposal presented by Boulder County Parks & Open Space that merges five conservation easements on a 1,500-acre property outside Lyons into one and allows the property owners, Paul Jonjak and Carol Potter, to build a 6,000-square-foot house on the land. At a hearing in December, members of the public expressed outrage. More than 20 individuals from across the county spoke. Every speaker except Jonjak and Potter’s lawyer and a Parks & Open Space staffer opposed the proposal.

Some neighbors of the property said the primary reason Esther May Sisk sold these easements to the county in the 1990s was to prevent residential construction on the property. Some speakers pointed out that although the value of this proposal for taxpayers is debatable, at best, Jonjak and Potter stand to make a killing if they sell the land as a 1,500-acre building lot. Others noted that this property is the only documented nesting site for Pinyon Jays in northern Colorado, and that the traffic, noise and lights associated with a large house would impact habitat for birds and other wildlife. Most speakers pointed out that the county would set a dangerous precedent if it seemed to rewrite the easements out of fear that Jonjak and Potter might sue. Some wondered whether landowners might hesitate to sell conservation easements to Boulder County in the future if the county can so easily be talked into undermining their core tenets.

Commissioners held a follow-up hearing last Thursday, March 8. Cindy Domenico was the only commissioner present who attended the December meeting; Will Toor was unable to attend in December, and Deb Gardner had not yet been appointed. On Thursday, Toor and Gardner said they had watched video of the December hearing. All three commissioners had also received a tour of the property. “The parcel is a tremendous piece of Boulder County,” Domenico said. “It’s beautiful, and it’s wonderful that we have it under conservation easement.” Then, without opening the March hearing to public comment, the commissioners unanimously approved the proposal.

Here are the benefits to taxpayers: The new easement limits agricultural outbuildings on the property to 15,000 square feet, whereas under the old easements non-residential buildings were limited only by the usual county Land Use processes. Having a house on the property may increase the likelihood that outbuildings will be built (there currently are none), but at least their size is specifically limited now. And that’s it; that’s the only substantial benefit I see.

Because the text of the new easement won’t be public until it’s finished and recorded, those of us following the proceedings have been relying on a series of Parks & Open Space staff memos to understand exactly what is in the new easement. The “Summary” section of memos dated Dec. 13 and March 1, in addition to a Dec. 16 memo designed to make corrections to the Dec. 13 memo, all include the sentence: “[The old easements] would be replaced with one new conservation easement that would prevent the Property from being subdivided, limit any non-residential outbuildings to 15,000 square feet, and define a two-acre building envelope within which all buildings must be located.” The word “all” in this sentence summarizing the benefits of the proposal made it seem that non-residential buildings would have to be located within the same building envelope as the house. This was another improvement over the old easements, which allowed outbuildings to be located anywhere on the property. However, in an email conversation with Parks & Open Space staff last Friday—after the decision was final—I learned that the building envelope applies only to residential buildings. The memos were incorrect. Oops.

The county also sees a benefit in eliminating the chance, which existed under the old easements, that the property could be sold as five separate parcels to five separate individuals, with “the potential for five different sets of management styles,” said Janis Whisman, Real Estate Division Manager at Parks & Open Space. And finally, the new easement would update the language of the old easements. Apparently in the ‘90s, Parks & Open Space lawyers wrote such ineffective easements that today’s staffers think it’s worth an enormous concession—a 6,000-square-foot house—to rewrite these 15-year-old contracts “to today’s standards,” as Whisman put it. Funny that staff in the ‘90s were confident enough in their contract-writing skills to spend $1.5 million of taxpayer money on this one.

In addition, Jonjak and Potter’s lawyer “disagrees” with the county about whether the old easements allowed for residential construction. I’ll try to make the explanation brief, but from a layman’s perspective it seems Jonjak and Potter have a weak case. The old easements explicitly prohibited “the construction, reconstruction, or replacement of any structures except as provided in Paragraph 3.” Paragraph 3 confined “the future use of the Property to agricultural/grazing uses and related structures.” Jonjak and Potter’s lawyer claimed each easement allowed for one house, for a total of five houses on this land. In December, he said that case law indicates residences are structures related to agricultural use of the land. On Thursday, the county let the public in on which case he was referring to: the March 2010 Colorado Court of Appeals decision in Shupe v. Boulder County, which includes the sentence “Once a parcel is determined to feature open agricultural uses, a single family dwelling, occupied by the owner, ‘will be considered customary and incidental as a part of this use.’” Although the easements allow it, the Sisk property does not currently seem to be used for agriculture. And the Shupe property was zoned agricultural, whereas the Sisk property was designated forestry by the old easements.

Perhaps zoning makes no difference (I’m admittedly not a lawyer), and Jonjak and Potter could easily start running cows on the land as an open agricultural use. But each of the old easements also contained a list of “prohibited uses and practices.” The first item on each list was “additional residences.” Jonjak and Potter’s lawyer claimed in December that this list “does not prohibit all residences. The use of the word ‘additional’ presumes that there already is an existing residence. And since there are no existing residences on the property, the ‘related structure’ language arguably allows the first residence on each parcel.” Huh? Would someone give this man a dictionary? The word “additional” means “added”; it doesn’t mean “more than one.” If I say, “I’ve bought a building lot and I’m planning to add a house,” what proportion of judges in Colorado would assume there’s already a house on my land because I used the word “add”?

Conrad Lattes, Open Space County Attorney, said on Thursday, “We have taken the position that the reference to ‘additional residences’ are residences in addition to what was there at the time that each of these conservation easements was granted to Boulder County. And if that is the way that it’s interpreted by a court, nothing in addition to zero is zero.” But there’s the rub. He added, “We believe that there is certainly risk and there is uncertainty as to what a court would decide.” Of course. Anytime you go to court, there is uncertainty as to what the court will decide.

When the time came to make a decision, the commissioners didn’t ask how much risk Lattes sees. They didn’t ask whether case law indicates that “additional” can be considered a synonym of “multiple.” They didn’t discuss possible negative consequences of approving the proposal, nor did they discuss whether the county had pursued any alternative solutions. Toor said, “My reading is that there is ambiguity in the language of the easement. The Shupe case did not seem like a reasonable outcome to me; I was quite surprised that a judge would rule in that way. And taking a look at that ruling makes me believe that in this case there would be substantial legal risk.” Domenico concurred: “I’m concerned that our risk is too high with the current easements as written. That ‘additional’ reference is problematic, and I think we are vulnerable based on the court of appeals decision in the Shupe case.” Deb Gardner agreed.

What about the precedent this decision might set for owners of other conservation easements who want changes to their contracts’ terms? Said Whisman: “We believe that this would not set a precedent. Other easements that have similar language also have additional language that is more clear, and different facts.” Said Toor: “I am reassured by the analysis from our attorneys that this is relatively unique language and that we would not be opening up an argument that other conservation easements should be modified.” Said Gardner: “This language is unique and isn’t setting a precedent going forward.” Said Domenico: “I think it’s been clearly stated that this would not be precedent-setting based on where we are with these particular easements versus all the other easements we have in place.”

And so it would be if saying something made it true. But the reality is that the commissioners sent a very clear message on Thursday: If you own a conservation easement in Boulder County and you want to change the terms, just find a lawyer who can convince the commissioners that there’s some degree of “risk and uncertainty as to what a court would decide.” Rattle your saber a little, and the county will be happy to rewrite that pesky contract.

So I have a message for Boulder County Commissioners: Stop wasting my tax money buying conservation easements. Lattes said on Thursday, “These conservation easements will continue to have tremendous value because we’re talking about whether to have zero, one or potentially five houses on property that, without these conservation easements, could have had at least 42 residences.” That sounds good for now, but it presumes that the county will actually fight if a future owner of this property legally “disagrees” with the county about whether he can add a second house, a third house, or a 42-home neighborhood. After all, the county paid $1.5 million not too long ago to ensure the number of houses would be zero.

I’m a big fan of conservation. But an easement is a contract, and the only way a contract has value is if it’s defended in court when its terms are threatened. If commissioners are unwilling to take the risk inherent in going to court, the easement is worth no more than the paper it’s printed on. If the county wants to preserve a piece of land, it needs to buy it outright. The $66 million the county has spent on conservation easements to date has not been a sound investment of taxpayer dollars.

(6 votes, average: 4.33 out of 5)

(6 votes, average: 4.33 out of 5)